Letter to investors – 2nd quarter 2020

Dear shareholders,

The second quarter of the year ended as one of the most unusual in the history of the financial market and in our lives. We went through one of the sharpest drops ever observed in history and with a very high degree of uncertainty due to the lack of information we had at that time.

We emphasized in the last letter that we should be careful not to perpetuate this extreme short-term situation in the long-term context. In this text, we will seek to explore this relationship between price, fundamentals and news a little more.

This quarter we experienced one of the most exaggerated periods both in terms of prices and in the distortion between long-term fundamentals versus short-term news. Thus, we can say that our investment process, oriented towards long-term fundamentals, has been severely tested, since at Moat we always seek to buy companies that have a rate of return on investment above the cost of capital in a relevant period. of time.

In the most acute moments of the pandemic, we observe many agents, as well as newscasts, with worrisome and bleak perspectives. At the same time, little was said at that time about the implicit price level of the assets. Even after we saw the sharpest drop (magnitude and speed) in market history, common sense was still one of heightened skepticism about the global economy and the direction of assets. It is also worth noting that, on many occasions when negative forecasts are confirmed, prices often behave differently than suggested by the news. Nevertheless, a justification for the decoupling of prices versus “fundamentals” is still being sought.

We always try to compare our estimate of a company’s cash flow with the price offered by the market. And, in most cases, the good opportunities are where the news and prospects are the least favorable in the short term. Thus, the purchase price of an asset is fundamental to our process.

Short-term shocks, like the ones we are facing, do not materially change the long-term capacity of assets to generate cash. We seek to understand the shocks that each company suffered from having its operations suspended or reduced and what would be the long-term impact on its business, in terms of competitiveness and capital structure. This math is not simple, since a small change in a variable can significantly change the share price. Since the beginning of the crisis, we have tried to treat the shock of the pandemic as a temporary event that, at some point in the future, would be overcome and would have little effect on the productive capacity of companies.

In the balance of risks, we remain concerned about fiscal dynamics and their possible consequences for the cost of capital. Since imperial Brazil, our rulers spend the taxpayers’ resources a lot and badly, and the cost of doing business in Brazil has always been too high. However, today we have a window of opportunity that is unique in history, given that we should have very low interest rates for a long time horizon in the world; as well as fiscal relaxation without long-term interest rates rising to reflect fiscal risks. This condition will not be permanent, but it may be vital for government officials to have time to resume the reform framework and the promised fiscal commitment.

Our country has never implemented reforms that offer a favorable fiscal condition to reduce the State’s weight in the productive sector. Thus, if we manage to consolidate the reforms (expenditure ceiling, social security, labor, tax and administrative reforms) we will have a significant decrease in the cost of capital.

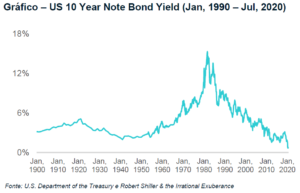

Since the great global crisis of 2008, the world has been experiencing lower and lower interest rates. The risk-free rate, calculated by the ten-year US Treasury bond, dropped to the lowest level in history, surpassing until the period of World War II, even though the US central bank substantially increased the money supply (about 5 times , since the beginning of the pandemic).

There is a huge debate among economists about how to exit this cycle, marked by the increase in the monetary base and asset inflation. Among the possible impacts, we can envision a recovery of economies at the expense of increased indebtedness over the years or, even, a scenario in which the stimuli from BCs and governments will have less and less effect and, thus, we would be close to runaway inflation.

The unraveling of the relationship between the US and China, strained after the pandemic, and the outcome of the American election will certainly have a major impact on the stock market in Brazil. A deeper change in global value chains, where companies seek alternatives to Chinese production, could create risks and opportunities for countries like Brazil. This will be a theme that should gain more and more relevance and we need to be aware of its consequences.

Predicting the market in the short term is impossible. If this rapid recovery in prices is not sustained by the resumption of activity and profitability of companies, we could see another sharp drop in prices. On the other hand, the pandemic being left behind, together with this environment of low cost of capital and stimulating, the movement of recovery could reach levels much higher than those negotiated today. We will always pay attention to the price paid for the assets and the discounted rate of return.

The profitability obtained in the past does not represent a guarantee of future results. Investments in funds are not guaranteed by the administrator or by any insurance mechanism, or even by the credit guarantee fund. For more information, access the website www.moat.com.br

Graciously,

Moat Capital